Remove the hijab, run to education - LET'S LOOK AT THE WORLD

In modern societies, development is not only measured by economic indicators; the level of education, women's participation in public life, and the strength of social institutions are also key factors. In this context, the question of what role religious symbols, particularly the hijab, play in public spaces is no longer merely a matter of individual belief, but raises serious questions related to social development.

Although discussions about the hijab in Azerbaijan have been conducted on an emotional level for many years, the picture becomes clearer when the issue is analyzed dispassionately within the context of development. While the hijab is presented as a form of clothing, its widespread adoption is often not the result of a woman's free choice, but rather of social pressure, patriarchal control, and radical religious influences. This directly weakens the development of human capital.

The situation in Azerbaijan is different, and this is a significant advantage. In the country, the hijab is not mandatory at the state policy level, and women's access to education is relatively high. However, this does not mean there is no danger. The transformation of the hijab into an ideological symbol, especially its imposition on young girls, and its presentation as a “measure of morality” create long-term risks for society. This approach reinforces a mindset that views women not as individuals, but as objects of control.

The historical context also shows that the hijab has never been purely a spiritual value. It has been used in various periods as a tool to indicate social status, sexual control, and to whom a woman “belongs.” While in modern legal systems all women are free and equal before the law, the mandatory preservation of this symbol loses its logic. Today, the hijab determines neither a woman's morality nor her social value. On the contrary, in many cases, it becomes an indicator that a woman does not have full control over her own life.

The most dangerous aspect is that the hijab often serves as a symbol that covers the main obstacles to development: weak education, economic dependence, and patriarchal thinking. The problem is not in the hijab itself, but in its transformation into a norm, a compulsion, and an ideological tool. Where women cannot make choices, development will not be sustainable.

When discussing attitudes towards religion, religious identity, and its public manifestations in Azerbaijan, it is crucial to clarify an important point first. The State Statistical Committee does not conduct official statistics regarding the religious beliefs of the population, specifically their religious affiliation, worship practices, hijab wearing, or level of religiosity.

This approach is directly linked to the country's constitutional foundations. The Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan establishes a secular state model in Azerbaijan. According to the Constitution, religion is separate from the state, and the state does not elevate any religious ideology to a superior position. At the same time, freedom of conscience is guaranteed. It is precisely for this reason that religious belief is accepted as an individual choice in our country and is not considered a subject of official statistical record-keeping.

The regulation of religious matters in the country and the implementation of state policy in this area fall within the competencies of the State Committee for Work with Religious Organizations. The Committee operates in the direction of registering religious communities, organizing their activities within a legal framework, preserving inter-confessional relations, and preventing radical religious influences. This Committee also does not keep any statistics regarding the use of hijabs.

One of the institutions playing a significant institutional role in Azerbaijan's religious life is the Caucasus Muslim Board. This organization, with historical roots, fulfills the function of preserving religious traditions in the region. Although the Caucasus Muslim Board is not a state structure, it stands out for its public influence and historical legitimacy in the religious sphere. However, it is also not the p that regulates this issue.

Fazil Mustafa, Chairman of the Milli Majlis Committee on Public Associations and Religious Organizations, states that although the issue of religion and the hijab has been a subject of discussion in Azerbaijan for many years, a situation at the level of a serious public problem has never arisen in this regard.

According to him, the sharp confrontations and deep social disputes observed in other countries have not occurred in Azerbaijan, and the main source of existing concerns is not internal.

“The problem is mainly being created by sectarian and religiously radical groups controlled from abroad. These groups have been trying for years to present the issue as one of Azerbaijan's supposedly serious problems. However, in essence, the topic has never reached a disturbing level until now.”

The committee chairman emphasized that in Islam, women covering their heads is related to ritual, but this concept should not be automatically equated with the hijab. According to him, the hijab is more a matter of culture and manifests in different forms among various peoples. Dress forms vary in Arab, Persian, Turkish, and other cultures. The form of dress consistent with the national traditions of the Azerbaijani people has never created a problem in the country.

“The promotion of the hijab or chador as an ideological symbol of a particular country goes beyond the framework of religious ritual and carries political-ideological meaning, which creates legitimate dissatisfaction in society. Women covering their heads with a simple kelaghayi or an ordinary scarf has always been accepted as normal in Azerbaijan. The problem only arises when this topic is politicized and turned into a form of propaganda directed from abroad.”

F. Mustafa particularly emphasized the importance of a principled stance regarding underage children. According to him, the mandatory covering of heads for underage children, whether in schools or other places, is unacceptable. The age of maturity in Azerbaijan is set at 14, and the compulsory application of any religious ritual to children before this age is not correct. Alongside this, it is possible to approach the beliefs and freedom of choice of individuals who have reached maturity and understand their choices normally.

The deputy added that the issue should be discussed within the framework of existing legislation, national traditions, and religious rituals, without being moved to an emotional and political plane. He emphasized that approaches such as “I will not uncover my head” when taking a passport photo are unacceptable and that such cases must be resolved in accordance with the rules established by the state.

Theologian Agha Hajibeyli, on the other hand, states that an increase in religious belief has been observed in various regions of Azerbaijan, especially since the period of independence.

According to him, just as people have returned to their national roots, they have also turned to their religious values, and this process has manifested itself in women's clothing choices.

“For many years, religion has existed in a completely free framework in the country. Whoever wanted to pray has prayed, whoever wanted to fast has fasted, and women have worn the hijab as they wished, and this has never been a subject of prohibition. Sometimes an impression of artificial restriction is created in this area, but these are not prohibitions stemming from the Constitution, but rather incorrect approaches formed by people themselves.”

The theologian emphasized that the idea that hijab-wearing girls should not go to school does not reflect reality. A sufficient number of hijab-wearing girls receive education in Azerbaijani schools, and the Azerbaijani state is the state of both hijab-wearing and non-hijab-wearing citizens. According to him, the main goal of educational institutions is not to impose restrictions based on religious attire, but to educate literate and intellectual young people. Neither the hijab is an obstacle to education, nor is not wearing a hijab an advantage: schools are considered the brain of the state, and the brains of the future are formed precisely there.

“It is also important to differentiate between the concepts of hijab and niqab. The niqab was more a form of dress specific to the Prophet's family, while the hijab was generally accepted for the wider community. Although the hijab is a command from Allah, it has not been presented as a compulsion throughout history, and a woman who adopts the hijab actually returns to her spiritual space.”

He added that the essence of the hijab is related to the protection and ensuring the dignity of women. Comparing this concept to the general order in the universe, Agha Hajibeyli stated that there is nothing in the universe without a covering and protection. The human p, nature, and even at the atomic level, a protective mechanism exists, and the hijab has been valued in this sense as a concept aimed at protecting women.

Journalist Vusal Mammadov, on the other hand, stated that the history of head covering goes back long before Islam. In ancient Mesopotamia, among the Achaemenids, and even in ancient Greek and Roman states, women from noble families belonging to the upper class covered their heads to distinguish themselves.

“In Assyria, by the same logic, a married woman absolutely had to cover her head. The logic is very simple. If a woman is for sexual use, the potential user must have the opportunity to see and approve of her. Therefore, in many ancient civilizations, women intended for sexual use were forbidden from covering their heads. That is, they could not cover them even if they wanted to.”

He noted that all of this happened before Islam. Islam, proceeding from the same logic, did not change the situation much.

“For example, in Surah Al-Ahzab, verse 59, it is stated: “O Prophet, tell your wives and your daughters and the women of the believers to draw their outer garments [jalabib] over themselves. That is more suitable that they should be known [as free women] and not be abused.”

From this, it becomes clear that the hijab is more a matter of social status than religious-moral: it is to distinguish a free woman from one who is not free. But the concept of “free woman” in Islam itself was different from today's. In those days, a “free woman” referred to a woman not intended for sexual use. An “unfree woman” meant that she could be fully used for sexual purposes.”

Now the situation is completely different. Now, thanks to the legal system created by humans, not by God, there are no concubines, and all women are free:

“There is no longer a need to distinguish between a free woman and a concubine. Therefore, the conditions and logic that made the hijab inevitable have completely disappeared. Today, the hijab expresses nothing: neither a woman's social status, nor her degree of freedom, nor especially her morality. In some cases, even contrary to classical logic, the hijab indicates that a woman is not free in terms of modern human rights, because many cover their heads due to pressure or psychological influence from male family members. I know many women who uncovered their heads after reaching maturity and gaining a certain degree of freedom.”

“As for official events and state institutions, I consider the use of head coverings unacceptable. After knowing what the hijab actually is, where, for what purpose, how, and why it originated, as we have discussed so far, it is simply shameful. What message does a woman wearing a hijab convey to those around her? Does she want to show that she is not a concubine, as stated in “Al-Ahzab, 59”? It is disgraceful, after all,” he concluded.

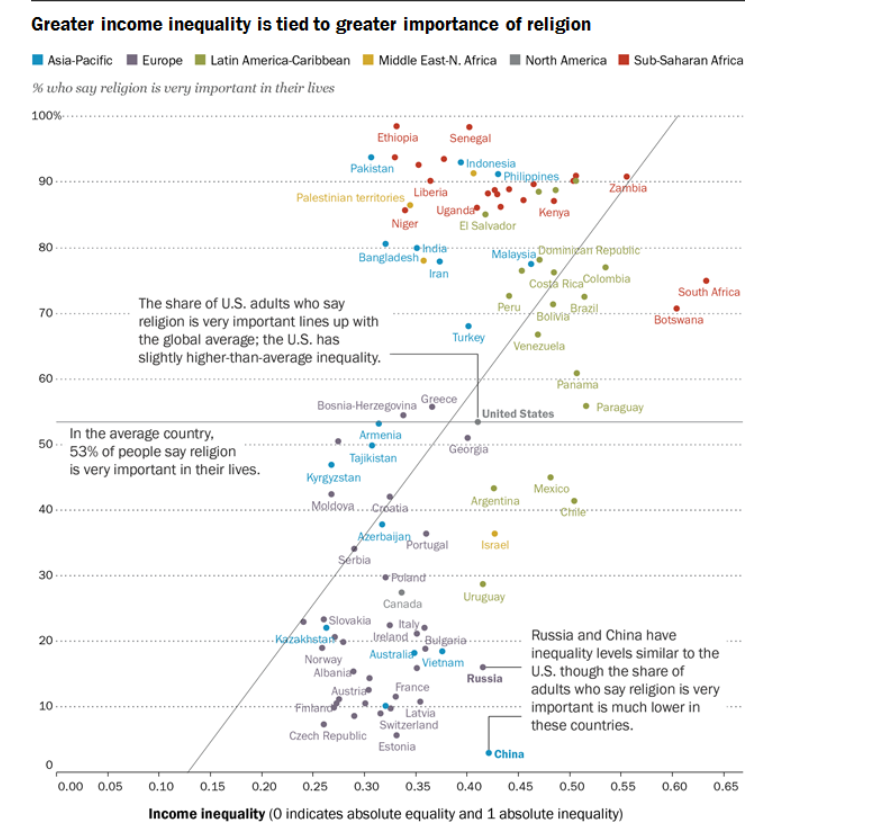

A number of international studies allow us to investigate this issue. According to information obtained from the “Pew Research Center”, a research center operating in the USA and recognized internationally as official and reliable, in countries with high income inequality, people are more likely to consider religion “very important.” Conversely, in countries with relatively higher socio-economic equality, the weight of religion in daily life decreases. According to the global average, approximately 53 percent of the population in most countries considers religion “very important” in their lives.

Azerbaijan is in the group of countries where religion is given relatively weak public importance in this landscape. The graph shows the share of those who consider religion “very important” in their lives in Azerbaijan to be in the 35-40 percent range. This indicator is significantly lower than both the global average and many Muslim-majority countries.

Interestingly, in this regard, Azerbaijan is on the same line as some post-Soviet and Eastern European countries, such as Armenia, Georgia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In these countries, although religion exists as a cultural and identity element, it does not act as the main guiding factor in daily life. On the other hand, a clear difference emerges between Azerbaijan and countries like Pakistan, Nigeria, Senegal, and Ethiopia, where both income inequality and religious importance are high.

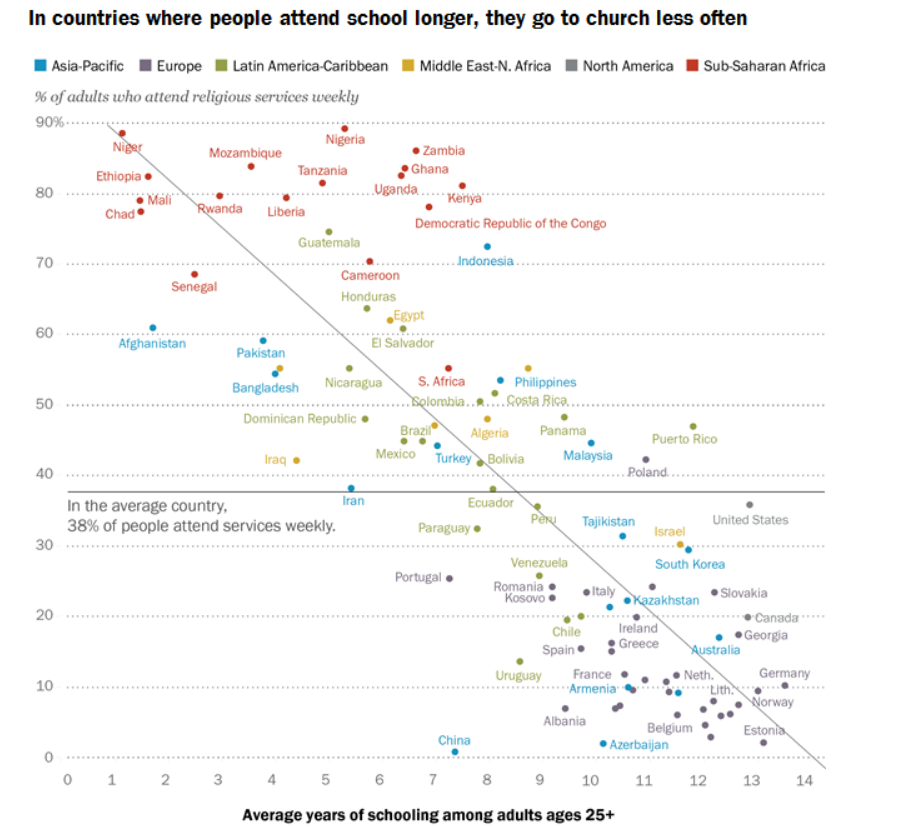

The research center also indicates a clear negative correlation between the duration of education and the frequency of participation in religious rituals. That is, the longer people are educated, the lower their level of weekly participation in religious ceremonies (church, mosque, etc.). In other words, it is very rare for an educated person to be devoutly religious. This shows that education and mandatory religious attire are inversely proportional.

In the global landscape, according to the average indicator, 38 percent of the population in most countries reports participating in religious rituals weekly. However, this average indicator is accompanied by sharp differences between countries. In African and some Asian countries where the duration of schooling and higher education is short, participation in religious rituals varies between 60-90 percent. In countries like Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zambia, both the years of education are few, and religion remains one of the central elements of public life.

In this context, Azerbaijan draws particular attention. The graph places Azerbaijan in the group of countries with an average education duration of approximately 11 years. This indicator is at the same level as many countries in Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet space. Weekly participation in religious rituals is shown in the 5-10 percent interval, which is significantly lower than the global average.

In this regard, Azerbaijan is on the same line as European countries with high educational indicators such as Germany, France, Belgium, Estonia, and the Czech Republic. For comparison, it should be noted that in Pakistan and Afghanistan, known as Muslim countries by religious identity, the duration of education is shorter, and participation in religious rituals is significantly higher.

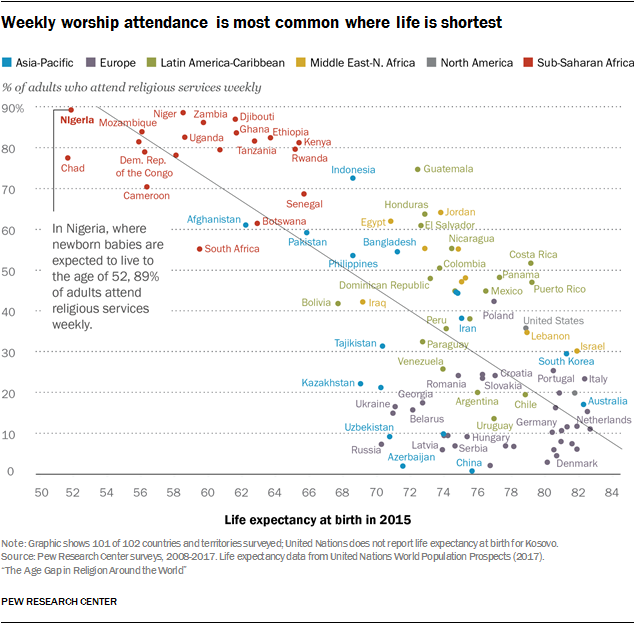

Studies show an inverse relationship between life expectancy and the frequency of weekly participation in religious rituals. The general tendency is that in countries where people live shorter lives, religion acts as a more central element of daily life, while as life expectancy increases, the intensity of religious practices decreases.

In countries located in the upper left part of the graph, such as Nigeria, Mozambique, Zambia, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, the average life expectancy is around 50-60 years, and 70-90 percent of the population in these countries reports participating in religious rituals weekly. For example, in Nigeria, the expected life expectancy for newborns is 52 years, and approximately 89 percent of the adult population regularly participates in religious ceremonies.

In countries where life expectancy is in the 70-75 year range – states like Pakistan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Egypt, Bangladesh – weekly participation in religious rituals drops to the 40-60 percent range.

In this landscape, Azerbaijan stands out with low religious participation and a longer life expectancy. The graph places Azerbaijan in the group of countries with an average life expectancy of approximately 72-73 years. In parallel, the share of those participating in religious rituals weekly is shown to be below 5 percent. In this regard, Azerbaijan is also positioned on the same line as countries with high life expectancy and low religious practice, such as Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark.

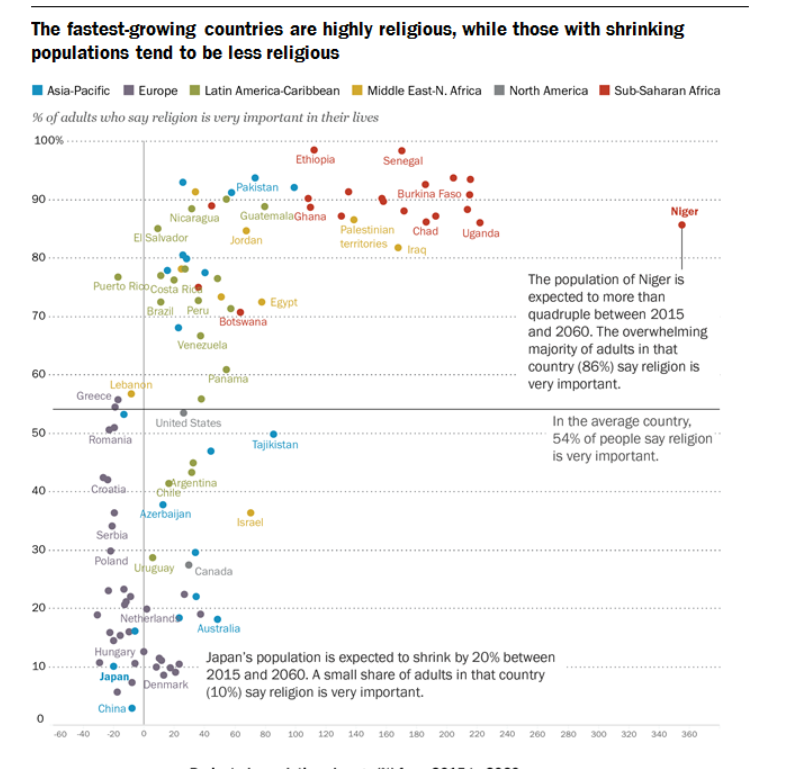

The graph above reveals a structural relationship between population growth rate and the importance of religion in people's lives. The general tendency is that in countries with rapidly growing populations, religion holds higher public and individual importance, while in countries with declining or stable populations, the role of religion in daily life weakens.

Based on the global average, 54 percent of the population in most countries considers religion “very important” in their lives. However, this indicator is directly related to demographic dynamics. In countries located in the upper right part of the graph, such as Niger, Ethiopia, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Uganda, and Chad, population growth is high, and the share of those who consider religion “very important” in these countries varies between 80–90 percent.

In this context, Azerbaijan is in the group of countries with low religious importance and limited population growth. The graph shows Azerbaijan among countries where the population growth rate is low, and at the same time, the share of those who consider religion “very important” remains at approximately 35 percent.

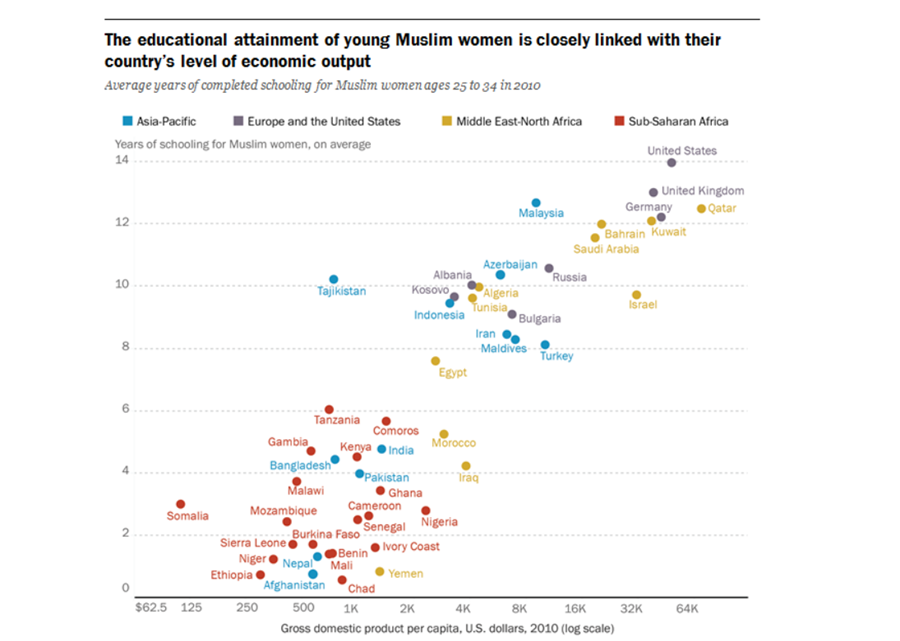

In the graph showing a direct relationship between the education level of Muslim women and the country's economic development indicators, the average duration of education for Muslim women, particularly in the 25-34 age range, increases as the country's GDP per capita rises. This means that as economic opportunities expand, women's access to education also systematically increases.

In countries located in the lower left part of the graph, such as Somalia, Afghanistan, Niger, Mali, Chad, and Ethiopia, GDP per capita is in the range of 500-1,000 dollars, and the average duration of education for young Muslim women in these countries varies between 1–3 years. Here, both economic weakness and socio-institutional limitations severely restrict women's educational opportunities.

In countries belonging to the middle-income group – states like Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Egypt, Morocco – as GDP per capita increases, the average duration of women's education rises to the 4-8 year level. At this stage, education is no longer an exception, but it has not yet become a universalized social norm.

In this context, Azerbaijan occupies a notable position in the graph. Azerbaijan is shown in the group of countries where GDP per capita is approximately 7-8 thousand dollars. Accordingly, the average duration of education for Muslim women aged 25-34 is approximately 10 years. This indicator is significantly higher than many Muslim-majority countries and forms a transitional position between Eastern Europe and Asia.

In this regard, Azerbaijan is located in the same cluster as countries like Albania, Kosovo, Russia, and Bulgaria. In these countries, although religious identity exists, women's education is accepted as an integral part of economic development and is promoted at the state policy level. On the other hand, higher-income countries such as the USA, Great Britain, Germany, Qatar, and Kuwait are located in the upper right part of the graph, where the average duration of education for Muslim women reaches the 11-14 year range.

Studies show that in countries where the level of education is low, economic opportunities are limited, political institutions are weak, and religion is radically drawn to the center of public life, social development indicators systematically lag behind.

Particularly in countries where religious ideology is directly integrated into state policy, where mandatory hijab is imposed on women, and their opportunities for education, labor market participation, and public life are restricted, the development of human capital is severely hindered. In these societies, the suppression of women's potential does not only become a problem of gender equality; it also acts as a structural barrier preventing economic growth, innovation, and social welfare. The absence of educated, working women participating in public decision-making lowers the overall pace of society's development. This is true within the family as well. And it manifests itself in society as a whole.

In this regard, it is no coincidence that in countries where radical religious norms are dominant, poverty levels are high, average life expectancy is short, and healthcare and education systems are weak. Here, religion moves beyond the realm of individual belief and transforms into a tool of social control and coercion. As a result, social relations lose their flexibility, the ability to adapt to changing global realities decreases, and development falls into a self-blocking mechanism.

When this picture is read in parallel with the above tendency, it becomes clear that development is not about the weakening of religion, but about preventing radicalization. As education and economic prosperity increase, religion loses its status as a social compulsion. Conversely, as radical religious frameworks strengthen, education and economic development are suppressed. There is a reciprocal effect here. Weak development strengthens radical religious approaches, and radical religious approaches further limit development opportunities.

Regulating this tendency, however, is extremely difficult. This is because it is not just about legislation or institutional reforms. Religious radicalization is fueled by social fears, economic uncertainty, identity crises, and problems of political legitimacy. Coercive mechanisms built around women's clothing precisely become visible symbols of these deep structural problems. In such circumstances, administrative decisions do not weaken radical approaches; on the contrary, they sometimes harden them further.

Consequently, the main line indicated by the studies is as follows: Where education, economic development, and institutional stability are strong, religion remains at the level of individual choice; where religion turns into a coercive norm and tool of compulsion, development halts. These two directions are not parallel but are processes that mutually shape each other. Balancing them requires long-term, multifaceted strategies that encompass all segments of society.

Finally, it is clear that Azerbaijani society is not problematic in this regard. Women themselves realize that mandatory religious attire stems from superstition. Sometimes, men rely on their wives wearing the hijab to feel secure. Considering the times we live in and its challenges, this seems very illogical. In any case, free choice is important here. Wearing the hijab merely as a display is actually not in line with religion. While respecting everyone's choice, we must emphasize one point: wearing the hijab does not make one well-mannered, moral, or religious. Nor the opposite. Wearing the hijab does not make one trustworthy either. The most important thing is to be knowledgeable, educated, and intelligent. Both a family and a society always need this. A country's strength comes from having educated mothers. A large number of hijab-wearing mothers does not contribute to this. It is gratifying that in Azerbaijani society, women now want to be scientific and educated, intelligent and business-minded. The future lies in science and education, in being intelligent and business-minded.

-

Today, 00:32The US destroyed 10 Iranian ships

-

Today, 00:24Russian diplomats were injured in an explosion

-

10 March 2026, 23:50When will the war in Iran end? - ANSWER FROM THE WHITE HOUSE

-

10 March 2026, 23:44"Galatasaray" achieved a historic victory

-

10 March 2026, 23:29140 US soldiers wounded in war against Iran

-

10 March 2026, 23:05Decision made regarding Saakashvili

-

10 March 2026, 22:59Pashinyan discussed the region with Macron

-

10 March 2026, 21:42Iran threatened Trump: "Be cautious!"

-

10 March 2026, 20:50The new leader of Iran, whose voice was heard only once: Mojtaba Khamenei's political portrait

-

10 March 2026, 20:25The number of injured in Iran was announced

-

10 March 2026, 20:16Prayer of the 21st day of Ramadan - Imsak and Iftar times

-

10 March 2026, 20:09Putin discussed the situation in the Middle East with Pezeşkian

-

10 March 2026, 19:34Body found in Cəlilabad

-

10 March 2026, 19:22Syrian President called Ilham Aliyev - Agreement was reached

-

10 March 2026, 18:57"Turan Tovuz" will play its home games in Sumgayit

-

10 March 2026, 18:40Ceyhun Bayramov received Oman's new non-resident ambassador

-

10 March 2026, 18:33Regarding Azerbaijanis who died in Israel, official information was released

-

10 March 2026, 18:17Prime Minister government members CONVENED

-

10 March 2026, 18:09No water in Maştağa for two days

-

10 March 2026, 18:01The names of three villages are being changed - LIST

-

10 March 2026, 17:40Israel came under fire - 2 Azerbaijanis killed

-

10 March 2026, 17:17Larijani threatened Trump: Be careful!

-

10 March 2026, 17:13Iran will be subjected to the most intensive attacks today

-

10 March 2026, 17:05Lavrov offered so-called support to Iran

-

10 March 2026, 17:03Costa will be in Baku tomorrow

-

10 March 2026, 17:01Top 10 districts with the highest increase in retail trade turnover - LIST

-

10 March 2026, 17:00Online ticket sales for bus travel have doubled

-

10 March 2026, 16:57Employees in this country have been permitted to work remotely

-

10 March 2026, 16:56Trump administration wants to end the war soon - Media

-

10 March 2026, 16:52Ter-Petrosyan sold Pashinyan - joined the Russian billionaire